In the 1890’s, when the first interurbans were built, farms could be, truly, isolated. In today’s age of automobiles and improved roads connecting almost every corner of the country, it may be hard to conceive just how isolated were most farms, even those within 20 or 30 miles of a large city. Even small towns mostly had a steam railroad, but for the farmer, obtaining supplies or getting crops to market could require day-long efforts.

When the interurban arrived, conditions for farmers could change quite suddenly. The nature of electric traction made it feasible for frequent trips and frequent stops, providing quick, direct service to every group of farms along or close to the line, a service that the steam roads couldn’t provide..

Furthermore, in regions such as Northern Ohio, this change took place just as cities were growing rapidly, creating a greater demand for farm products. The economic change for the farmers was considerable. In the past, isolated farmers needed to be largely self-sufficient, with cash crops confined mostly to things such as grain, that could be transported cheaply and wasn’t damaged by slow shipping and rough handling. Now, ready accessibility to growing, hungry cities made production of high value, perishable dairy, meat, fruit and vegetables a very profitable endeavor.

Thus, crops changed as farmers specialized in a single cash crop, and farm incomes increased markedly. In turn, new-found income made farmers ready customers for now accusable city activities and manufactured goods. This change made possible by the interurbans occurred several decades before trucks and automobiles connected farmers to the city.

This post is largely based on Hambley, S., “The Pioneer Route and Electric Railways of Northern Ohio,” available through the NORM shop.

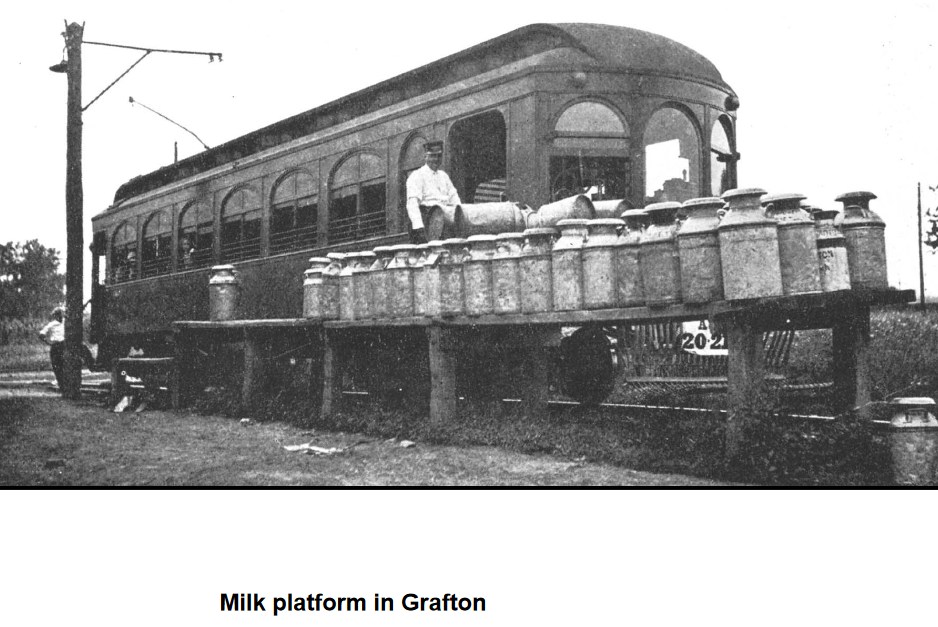

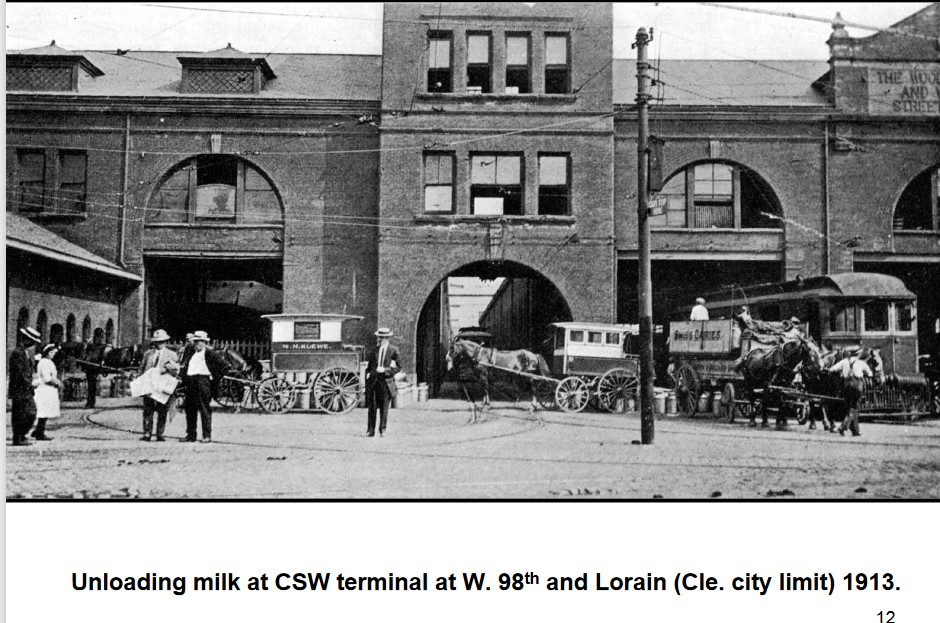

Pictures, all Ralph Pfingsten Collection/NORM Archive, show 1) Cleveland Southwestern (CSW) milk platform at Grafton, 2) Milk being transferred at CSW Cleveland Terminal and 3) Milk being unloaded at CSW Cleveland Terminal.